Cnhi Network

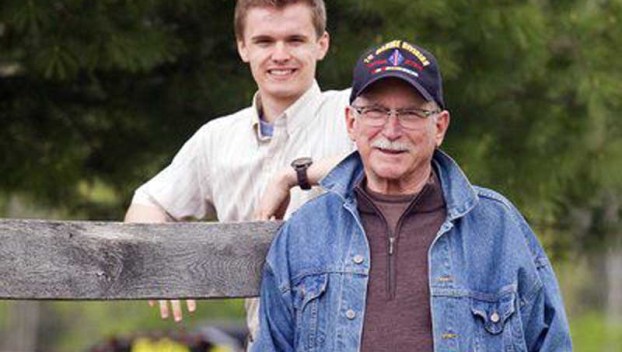

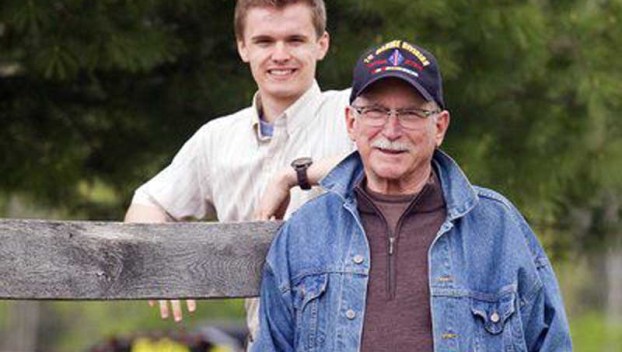

Young filmmaker documents veterans’ difficult return from Vietnam

A group of five Vietnam War veterans, including Larry Lelito, collaborated to share their own homecomings and describe ... Read more

A group of five Vietnam War veterans, including Larry Lelito, collaborated to share their own homecomings and describe ... Read more