Community

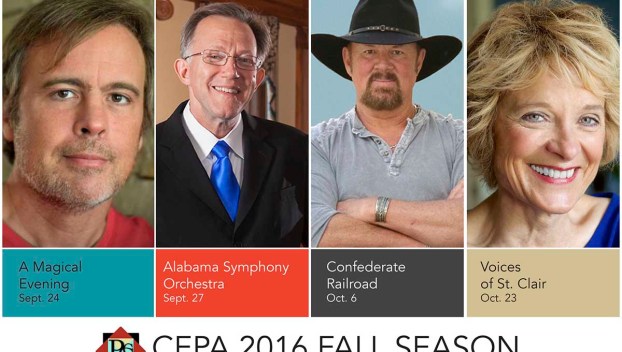

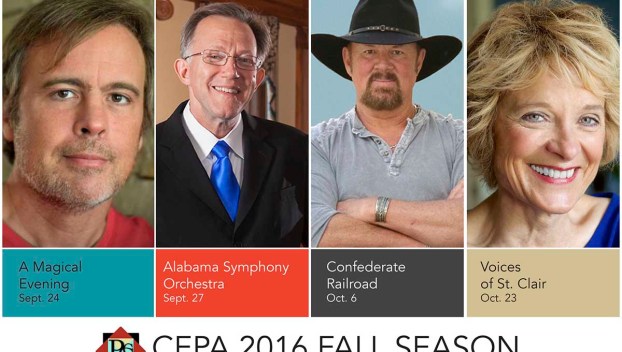

CEPA 2016 Fall Season Tickets on sale Monday, July 18

Next week, tickets go on sale for the one of the most exciting seasons ever at the Pell ... Read more

Next week, tickets go on sale for the one of the most exciting seasons ever at the Pell ... Read more

The war was over, but Ike Murphree needed to reach for the hand of God one last time ... Read more