Rare as rainbows: St. Clair resident shares memories as female pilot, flight instructor

Published 12:00 am Thursday, June 22, 2023

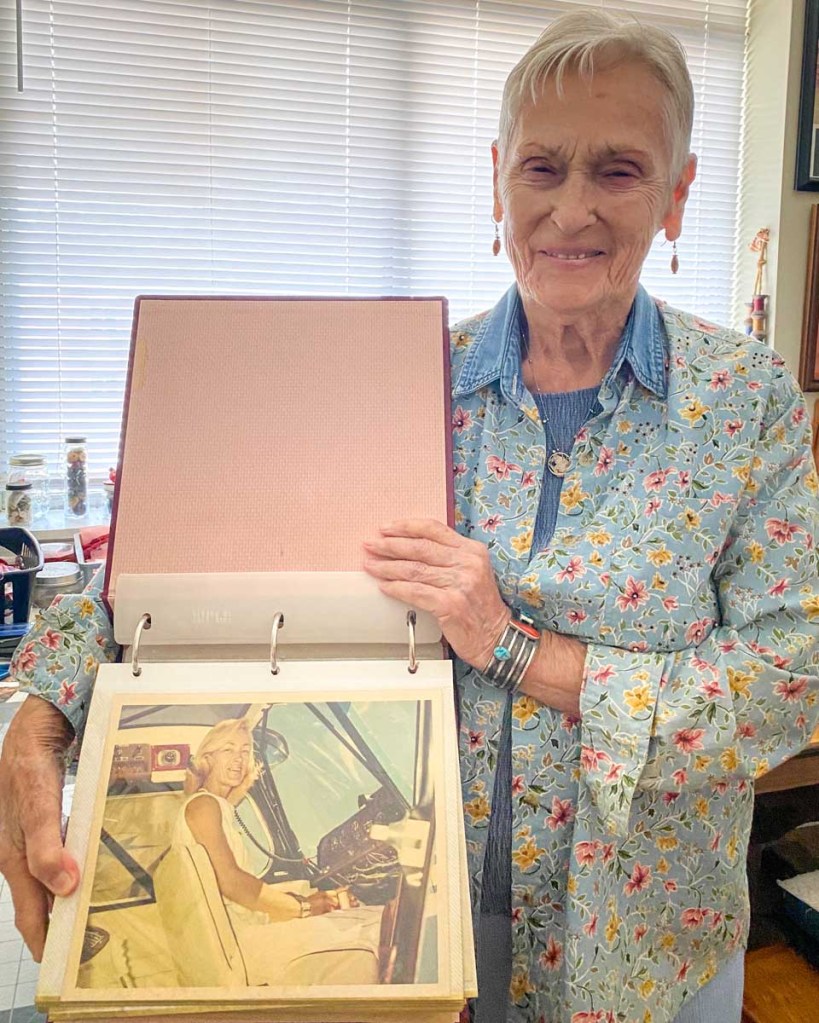

- Shirley Parker with displays of some of her memories from a life of living as a pilot. Robin DeMonia for the St. Clair News-Aegis

A lifelong fascination with flight began when Shirley Parker visited a dirt airstrip in California with her father and brother as a young girl. Parker watched the barnstormers and crop dusters circling the skies and she immediately wanted to be where they were.

“One day, I’m going to fly,’” Parker told her dad.

“Sure you are,” he answered, no doubt assuming this childish flight of fancy would pass.

Little did he know that his daughter would indeed grow up to fly airplanes — and would teach many others to fly airplanes, too, at a time when female pilots and flight instructors were as rare as rainbows in the sky.

“I just couldn’t get enough flying,” said Parker, now 89, and an independent living resident at the Village at Cook Springs who moved to St. Clair County to be near her son.

“Once you fly, it gets a hold of you. Or at least it did for me.”

The beginning

Parker was born in San Jose in 1933, the year after Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. But Earhart’s achievement didn’t unleash a torrent of women in aviation.

By 1960, when Parker’s childhood dream was just starting to take flight, women still made up fewer than 3 percent of pilots and fewer than 2 percent of licensed flight instructors, according to the Federal Aviation Administration. Today, women make up fewer 10 percent of pilots and flight instructors.

When Parker finally set out to earn her wings, she was already a young mother and wife. Her husband, Otis “Tex” Parker, was a tall Texan who’d come to California for the Navy and who wasn’t the least bit bothered when his wife confessed over dinner she wanted to learn to fly.

Without a second’s hesitation, he told her to go for it, and he also encouraged her to approach two neighboring diners who’d been talking about airplanes. That introduction led her to Garden City Aero at Reid-Hillview Airport, where she’d spend the next two decades advancing her skills as a pilot and helping others to develop their skills, too. She rarely turned down an opportunity that meant spending more time in the sky, and ultimately got a commercial license and instrument rating as well.

Though Parker has long since left the cockpit, her home at the Village at Cook Springs is filled with memories of those days. There’s a scrapbook full of photos of planes and young Shirley back when they called her “Sparker.” Scattered around her apartment are aviation posters, model airplanes and her old log books.

The memories come alive as she shares the adventures that began after she showed up for her first flying lesson and experienced a second of hesitation — a short-lived flutter that evaporated as soon as she went wheels-up.

“I did well,” she said, recalling her first lesson. “I loved every moment of it. Even the ones when things were a little scary. I didn’t want to come down.”

It took her two tries to pass the written exam and months of training in takeoffs, landings, stalls, spins and other maneuvers before the chief pilot deemed her proficient in her skills.

“I knew when he turned me loose to fly solo, I was ready,” she said. At the end of all that, she found herself surrounded by well-wishers, looking at a “big gizmo of champagne,” and holding a license to fly a plane.

The next step

The idea of going a step further and becoming a flight instructor came from those who taught Shirley to fly. Garden City thought it would be good business to have a woman instructor to teach other women. But as it turned out, she ended up training women and men, including Tex.

“I taught my husband how to fly and stayed married,” she said.

Some men resisted a female instructor at first, but they got over it.

“Once I flew with them, I couldn’t get rid of them,” she said.

In fact, some male students liked her too much — some got fresh to the point that she declined to continue as their instructor. But in most cases, she was able to get them to turn off the charm and get down to business.

“I learned how to turn the gas off,” she said.

Some needed her tough love in other ways, like the “spit and polish” Army Captain who thought he was ready to get his pilot’s license in three weeks and vastly overestimated his skills. Parker put him through the paces — so much that when they were done, the sweating captain himself suggested he might need a little more training. She assured him he needed much more training, and to her great surprise, he asked her to do the honors.

Asked what makes a good pilot, Parker doesn’t hesitate.

“Having respect — respect for the aircraft, respect for the instructor, respect for the rules and regulations,” she said. “You have to have the utmost respect. If you don’t, keep away from the aircraft.”

At the end of the day, she had one goal for her students, and she passed with flying colors.

“None of my students flunked,” she said. “They all passed.”

Flying higher

Parker loved the adventures associated with flying. There were chance encounters at the airport with celebrities such as Jane Russell and Chuck Yeager, and even a passing glimpse once of the elusive hijacker D.B. Cooper. She was endlessly fascinated with aircraft and vividly recalls the moment she first saw a 747.

“They told me they called it the Messiah, because the first time you saw it, you got to your feet and looked up like it was the Second Coming,” Shirley said.

But above all was the joy of flying itself. She loved the thrill of aerobatic stunts like loops and rolls, and the ease of travel when air traffic was not quite as controlled as it is now. It was not uncommon back then for Parker and her family to hop on a plane for a 15-minute flight to Napa to eat at a restaurant known for its good steak dinners.

She was willing to try anything that involved flying. She once made an appeal to join a team of aerial firefighters, but they rejected the idea of a woman in the role. But her gender usually was not an obstacle.

Once, the district attorney asked for a pilot to fly a photographer over a murder scene, with one catch — he wanted the doors taken off the plane. Unlike her male peers, Shirley said yes and circled the scene again and again, the photographer sitting at the open door and snapping away.

“They found out I would do just about anything,” she said.

The only close call she recalls involves a time when another plane was intentionally “buzzing” her and a student pilot. She later reported the pilot who had flown into their space, but the close brushes were harrowing.

“It scared my student to death,” she said. “It didn’t do me any good either.”

The sky is the limit

Being in the cockpit was not all adventure and fun. Some of the most powerful memories Parker shares are poignant moments where flying opened the door to mysteries of mortality and immortality.

One of her students and his wife lost an infant who’d been conceived after months and months of trying. The father asked Parker to fly the child’s ashes and spread them over the Monterey Bay. That was one flight she never forgot.

Then there was a stream of college ROTC students in the 1960s who were learning to fly. Parker knew why, and she didn’t like it.

“That was kind of heartbreaking for me because I was training them to go to war,” she said. “My boss told me, ‘Somebody has to train those kids, and you’re the one I can trust.’ So I trained the snot out of them.”

She is still haunted by questions, though, of whether they survived Vietnam.

If her memories include heartbreak, they also include indescribable beauty.

One of her favorite things to do was fly on New Year’s Day.

“Everybody was home with a hangover,” she said. “I’d have the whole sky to myself.”

She recalled being on top of the clouds some of those days, with the sun behind her and halos and rainbows enveloping her.

“I can still see it,” she said, her eyes filling with tears and her hands rubbing the goosebumps that appear on her arms. “I think that’s the thing I miss most is being alone with God up there. That’s his domain.”

She relates her experience to those captured in a poem that closes out the book “God is my Co-Pilot.” The poem, written by a fighter pilot, ends: “I’ve trod the high untrespassed sanctity of space, put out my hand and touched the face of God.”

Nearing the end

But by 1981, she was ready to give it up. Tex, who worked for IBM, was being transferred to Tucson. and airports had somehow become more sinister. Law enforcement officers were encouraging Parker to carry a gun and learn how to use it, and giving her pointers for how to fend off someone attempting to commandeer her plane. Some of the issues were related to drugs.

“I went out one day and I found a roach on the floorboard of the plane,” she said. “Do you know what that is?”

The snuffed-out marijuana cigarette on the floorboard was just one sign of the times.

“Things were changing, and I didn’t like it. You couldn’t trust people anymore,” she said.

She decided it was time to come down from the sky.

Today, her airplane memorabilia is crowded by a sewing machine, quilting table and scraps. But she seems to rise aloft once more as she shares memories of a young pilot who was, without question, hot stuff. Her eyes light up, and the stories spill out, and she says again and again she’d like to take you up for a spin.

“I’m not one to keep my feet on the ground,” she said.

But only her heart is still up there in the sky. As for the rest of her, she said, “Logbook closed.”