Fox recalls horrors of war

Published 2:51 pm Friday, October 28, 2011

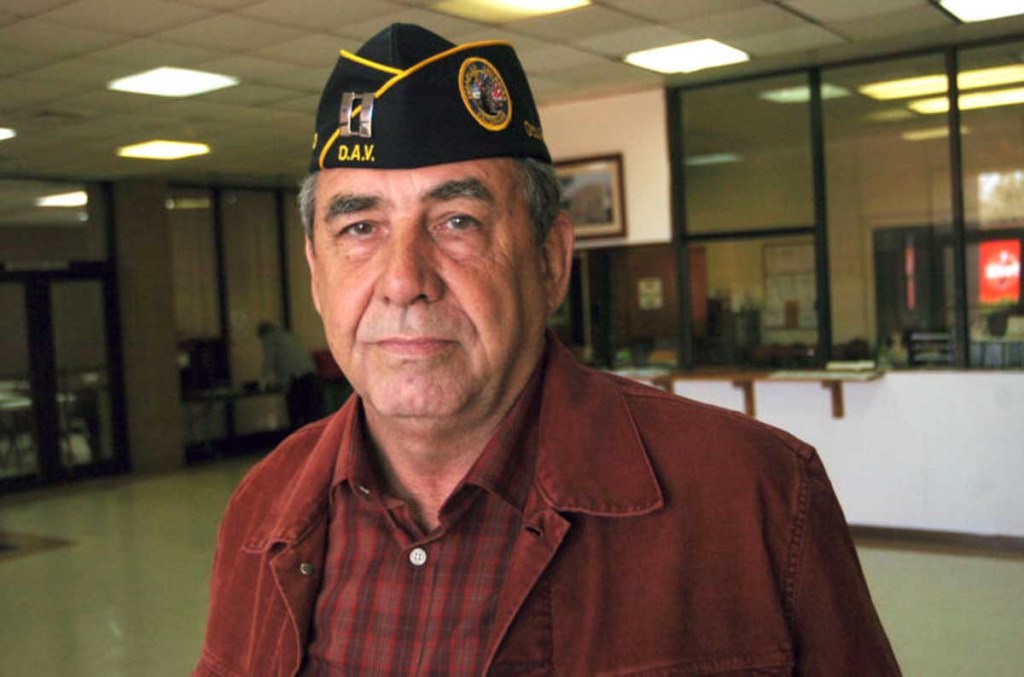

- Vietnam veteran Cpt. Otto Fox will serve as master of ceremonies during Pell City’s Veterans Day observance on Nov. 11. He works with a number of veterans’ organizations, including Veterans of Foreign Wars, Disabled American Veterans, and the American Legion.

Otto Fox isn’t one to wax patriotic about his military service, but he’s a staunch champion of those who have served.

“My only issue is veterans,” he said. “This country’s wealth is not in its money or its politicians. It’s in its veterans. Before we ever had a dollar bill with Washington’s face on it or a preamble to the Constitution, we had veterans.”

His passion for veterans’ causes stems from his own experiences during and since the Vietnam War, in which he served as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army from 1970-72.

As a graduate of Banks High School, “we had the choice of being drafted into military service or go to college and hope the war ended before we finished,” he said. By the time Fox was a junior in 1968, American deployment to Vietnam was at its height, with more than one million servicemen there.

The story of the war goes back to more than a decade earlier. “Back in the 50s, communism was our big enemy,” Fox recalled. “Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon all saw the influence China and Vietnam were beginning to have, and they felt we had to go and make a stand. We would not allow them to take over.”

What may have started as a noble cause soon gave way to the realities of war, as Fox found out after receiving his commission as an officer.

“We’d never fought guerilla warfare before,” he said. “They were taking young people such as myself and putting us in the jungles of Vietnam with training and weapons that were not adequate. We were developing weapons as we were fighting. The need for weapons in Vietnam was greater than the need for training in the States, and any training you had didn’t mean anything when you went into the jungle. It was remarkable what a cruel animal you could become.”

Acknowledging that no soldier had it easy in Vietnam, Fox said that combat veterans were affected more than those who had support assignments.

“The worst thing that can happen to a solider is that he remembers he has a mother. A combat solider has to think about nothing but killing. In World War II, in the South Pacific from 1943-45, the average soldier spent 21 days in combat. For a Vietnam veteran, the average was 211 days.”

Fox often uses a comparison to illustrate the effect combat has on veterans.

“Take the finest steak you could ever buy. That’s your human brain. Then you take a grill and turn it on as hot as it’s ever going to get. You put that steak directly on the grill and don’t take it off. When you put a fork in to turn it, it’s seared to the grill. When you try to turn it, it rips apart. That’s what combat does to a soldier.”

Fox returned from combat at a time when America was dealing with the fallout from the My Lai Massacre and the Kent State shootings.

“I came home from combat, but the combat solider never left the jungle,” he said. “I’ve had doctors ask me, ‘How often do you think about Vietnam?’ There’s hardly a waking moment in my life when I don’t think about it. They’ve asked me, ‘Do you remember your fraternity or Christmases when you were growing up?’ I don’t. I couldn’t take you to the house in West End where I grew up without asking for directions, but I can take you down trails in Vietnam right to the exact point where we set up an ambush or a chopper was shot down.”

Fox, who left active duty as a captain in 1978, said the experience is not unique to him.

“I go to veterans’ hospitals often, and I see veterans who are so far out of the mainstream, who are so on the edge. America has not been there for these veterans 24/7 like we required them to be in combat. We all lost friends and relatives in Vietnam, and there were as many people making a fortune off the war as there were families losing loved ones.”

Lack of discipline and control also plagued American efforts in Southeast Asia, he said. “There was no control at the top. Discipline has to come from the top. You never saw a colonel on the battle lines, and our best did not go to Vietnam. Our Princeton and Harvard graduates, who could have made a big difference in Vietnam, either fled this country or deceived this country.”

He recalled talking with one person who told him that he falsely claimed to be attending medical school after finishing college so that he could receive a deferment to avoid deployment to Vietnam. “It bothered him. He told me his story years later because he wanted to clear his conscience.”

While serving, Fox said he felt a keen responsibility to the soldiers in his command, a weight he still carries.

“You took care of your men. You didn’t let anything happen to them. All you had to do was put one of your men in a body bag, and you weren’t right. I wanted to believe that they hadn’t died in vain, but as the days turned into years and the years turned into decades, I’m still haunted by the memories.”

A particularly haunting memory is the way orders were issued.

“They’d say, ‘Lieutenant, take 17 men out there and see if you can find them. If you find them, kill them.’

“’Kill who?’

“’Whoever you find. If they’re out there, they must be the enemy.’

“We used to have a saying, ‘We’ll let God separate them.’ That was the Vietnam War.”

[Editor’s Note: Cpt. Fox requested that News-Aegis readers know that Buddy Roberts’ father was Army Spc. Gordon E. Roberts Jr., a Purple Heart recipient who served as a heavy equipment operator at Da Nang, Vietnam, during the Tet Offensive in 1968.]