(Author interview) Bridging baseball: Sandra W. Headen’s debut novel intertwines segregation, friendship and determination in a transformative story for all ages

Published 4:00 pm Wednesday, June 19, 2024

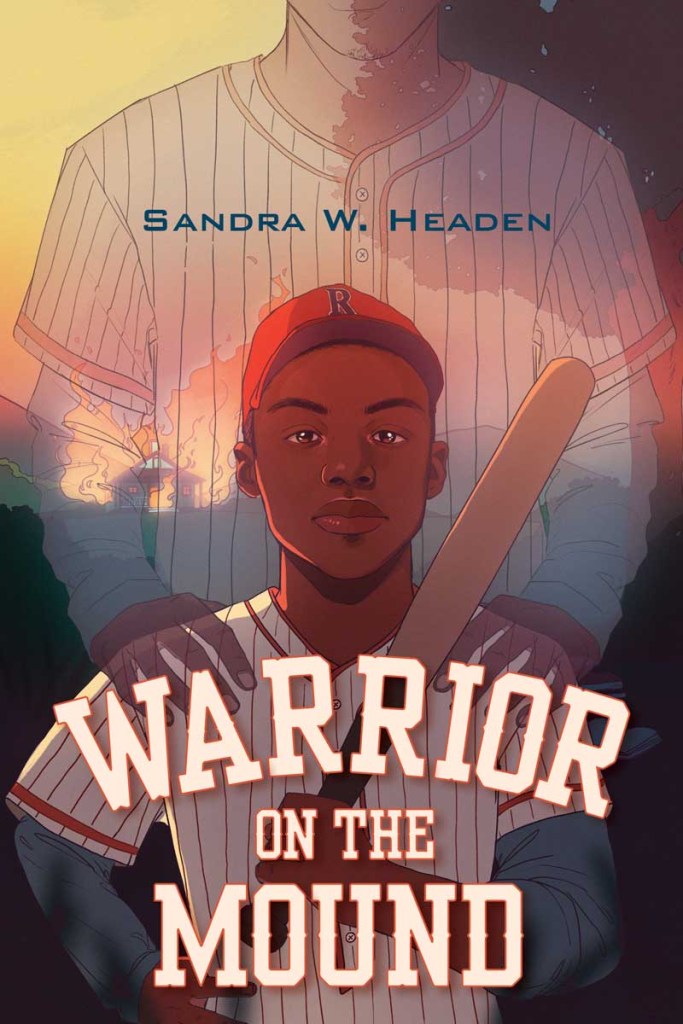

- 'Warrior on the Mound' by Sandra W. Headen.

How history repeats itself: Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama — the oldest ballpark in America — scheduled a game June 20 between two Major League Baseball legacy teams, the San Francisco Giants and the St. Louis Cardinals, connecting the field’s 114 years of baseball history, and paying tribute to both the Negro Leagues and the person many consider the sports greatest living player, Hall of Famer, Giants legend, Birmingham native and Birmingham Black Barons star Willie Mays.

Mays, at 93, died two days before the game would be played, but he did previously express, in a single quote on the Giants’ website, how the game of baseball has connected people for more than a century: “I can’t believe it. I never thought I’d see in my lifetime a Major League Baseball game being played on the very field where I played as a teenager.”

Which brings us to 2024 and Sandra W. Headen’s prescient debut novel about a Black tween in North Carolina who aspires to follow his older brother and deceased father into the Negro Baseball Leagues. Set in 1939, “Warrior on the Mound” (Holiday House) details the first-person narrative of Cato Jones as he and his team trespass on a new — and whites-only — ball field, only to be falsely accused of causing damage.

Even at 12, Cato knows he’s in no position to challenge a white person’s lie, but from the incident he does learn that the owner of the field and his father, legendary Negro Leagues ballplayer Daddy Mo, were once friends. From there, the unraveling of his Daddy Mo’s murder, the racially motivated beating of Cato’s brother, Isaac, and the community discords of the period spur the story toward a game between two Little League teams, one white, one Black, that will either tear apart the community or seed healing relationships.

Headen’s engrossing novel — a blending of history, sports and family into a coming-of-age story that should be on every required reading list this summer — skillfully weaves historic and actual facts. The result: A deep and honest dive into a period of racial disharmony that propels a dialogue toward home plate.

Expanding on that dialogue, Headen agreed to answer a few questions about her novel. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tom Mayer: Sandra, I want to start with this. I honestly believe that “Warrior on the Mountain” just might be the most important book that anyone of any age could read this year. Does that resonate with you at all?

Sandra Headen: It does in part because of the reactions I’ve gotten from different kinds of people. I started out talking to a high school group of students, and I’m on the board of directors of this high school, and the adults were just as excited as the kids, maybe more so. So yes, I mean, that’s what I thought when I wrote the book and I’m really glad to hear you say that.

TM: What’s interesting is that you could have written this book and its subject on many different levels, but you chose middle school readers. Why this age group?

SH: Well, I’m a social psychologist, and I’ve worked in the field of public health. The area I worked in was tobacco-use prevention. It was in the late ‘90s, early 2000s, and I was a part of a national movement to decrease the use of tobacco in America to decrease mortality and morbidity from tobacco. One of the programs that we had was targeted to middle graders. And so for seven years, I worked as a consultant with the state of North Carolina on a [youth] initiative. It was a peer-education program where the public health professionals worked with youth groups, community youth groups … and we were training them to conduct peer education programs in their communities to help keep kids from starting to smoke. … So, that influenced me a lot to think about the fact that the time when people are really influenced is during the middle grade years. That is when I was most influenced. I remember being in eighth grade and being impacted and changing a lot of my attitudes about a lot of things about people and the world.

I also I have to tell you, my initial career goal was to be a middle school teacher. So when I graduated from college, I … was getting a master’s in education and also teaching in New Jersey public schools. That didn’t work out for me, but I never forgot the kids that I worked with.

TM: You certainly remembered well. I will say that I was not a 12-year-old boy in 1939, but I can think back to when I was 12 and it certainly resonates with me, now. Something else that resonates with me, Sandra, is that you make it clear that while the story is fictional, some of the characters are based on real people, and you explain in an appendix some of the names you chose to use. But what I’m wondering about, beyond the people, are some of the relationships in the book and if those are based on real people — because this is the real magic of this novel. You create a secure, nurturing world in a place of segregation, extreme violence, bigotry and hatred, but that nurturing place seems very, very real. Where did these relationships between Cato and Grandpa Vee, Hope, Luke, Rev, Trace and others come from?

SH: My homes. The homes I grew up in. First of all, my grandfather and my grandmother just established a very welcoming and warm home. What people don’t realize is that even in segregated times, Black children were often insulated from a lot of things. Some were not, many were not, but many were. I grew up in Greensboro, North Carolina, which is the Piedmont area. It is, you know, the home of many colleges. … So it’s a different kind of environment. I felt that, after I grew up, I know that I was insulated from a lot of the racism that was going on at the time. I lived right down the street from my elementary school, my middle school and my high school. And I had a five-minute walk to school. My father worked at the post office, my mother was a hairdresser. … My grandfather was very strong; I call him fearless. I mean, in a time when people might call a Black man boy, everyone called him Mr. Arthur. Wow. And I thought, wow, you know, there’s something different about this. He could read at a time when many of the people in his church could not. So no, my grandfather was different, you know, and it was very close. So the relationships in the book reflect the relationships in my nuclear family in Greensboro and in my grandparent’s home in Wilmington, where they were raising their grandchildren. And I went to visit them every summer. And we stayed anywhere from two weeks to a month and it had such a profound influence on me. And that is why my debut novel is not about the home that I grew up in, but the environment that my grandparents created.

TM: Why set the novel in 1939?

SH: The kids I’m trying to reach. I wanted the era to be pre-war and I wanted to find an era that I could, in some sense, relate to that was not so far ago. So, I didn’t want it to be my grandfather’s childhood, because that would have be a little too foreign to me. (In the story) my grandfather is actually Papa Vee. My grandfather’s reflected in Cato’s grandfather. I was born in ’47, so I figured I could I pick a time that I could relate to and do some research and recreate that world for everyone. Now, the specific year 1939 is because there’s a scene in there where Gran (tends) the wounds of Isaac, her grandson, after his injury, and I discovered that the fishing line that was used in that scene was not available to the public until the year 1939.

TM: I wouldn’t have guessed that answer. The friendships that develop between Cato and Trace and finally Luke and Rev are born out of forgiveness and a willing to go past the personal and kind of societal ignorances that they were dealing with at that time to keep them separated. And this was 1939. So this is a difficult question, but how are we still dealing with the same issues today — and what do we do about it?

SH: Well, that is a hard question, and I don’t have an answer. I can’t tell you how those friendships exist in the book because I’m not sure I got this accurate as a child as I look back on it. My grandfather had … a man who used to come by, a white man, who used to come by and help him do things. And I perceived them to be friends. Later, it wasn’t so (clear) they were really friends. But I perceived them to be friends and I thought, oh, that’s interesting, and I grew up thinking that they were friends. So that was one piece of information that went into my making the friendships in the book. I had a writing teacher who told me about bridge characters … and she said it would be very interesting if you had a character who had his foot in both cultures. And that made me think of the white man that might have been my grandfather’s friend.

TM: Those relationships make for a very optimistic story. Devil’s advocate: Is the story overly optimistic for the time period … or even today?

SH: Well, I think when you tell a story, especially for the middle grade age group, or for any age group, it’s the author’s privilege to tell us what the future can look like. And human beings have many possibilities. And so solving these problems, the one you asked me, well, you know, how do we solve this? I don’t know. But human beings have many characteristics, many qualities, and some of us will solve the problem.

TM: That’s a wonderful answer, and that is exactly why I said earlier that this is probably the most important book that anybody could read this year. Similarly, sports can be a common denominator for diverse groups, races, men and women, a lot of different groups. In this novel, you make that happen in the story itself, but also in the history of baseball. Is there anything kind of analogous to that today — sports or otherwise — that would actually bring groups together?

SH: You know, unfortunately, we’re not moving forward right now. In fact, it’s harder for me to watch baseball this year than it has been in the past because the percentage of African Americans in baseball is declining. It’s about 6 to 8% now. (It’s) the structure of the game now, how you get to a major league team and the amount of money it costs for kids to be players in high school and college. I have a colleague whose son is in baseball and in one year, he just casually told me, he said, wow, you know, I must have spent $15,000 on his baseball this year. And you know, I’d say that was fine. You know, I never look at an individual and try to make global comments. He’s just dealing with what the situation is. But I thought, boy, we’re going in the absolute wrong direction If it takes that amount of wealth for a kid to be in baseball.

TM: Talking about kids in baseball and aspiring for the major leagues — you must have been working on some stage of the novel when they announced the game at Rickwood Field in June. Did that influence you at all?

SH: One of the things I talked about during my (book launch) at Quail Ridge Books which surprised me, actually, was to see where my notes, historical themes and contemporary times (intersected). … So the game in Birmingham is in that vein. … That the contributions of the Negro League players and the existence of the Negro League are being recognized now, I see that game as a recognition of that.

TM: I’m glad you got to launch the book at Quail Ridge. That’s a wonderful independent bookstore in Raleigh, North Carolina.

SH: I discovered it when I first moved here, My husband taught at NC State, so it was nearby. I used to go in and see the photographs of the authors on the wall and I thought, oh wow, it would be wonderful to be there.

TM: And now you are.

SH: When all of this happened I was just overjoyed. Even though I have another career, what I wanted to be all my life, and my mother will tell you this: I always wanted to be a writer.