BLACK HISTORY MONTH: Black authors keep history alive amid efforts to ‘suppress Blackness’

Published 11:00 am Wednesday, February 1, 2023

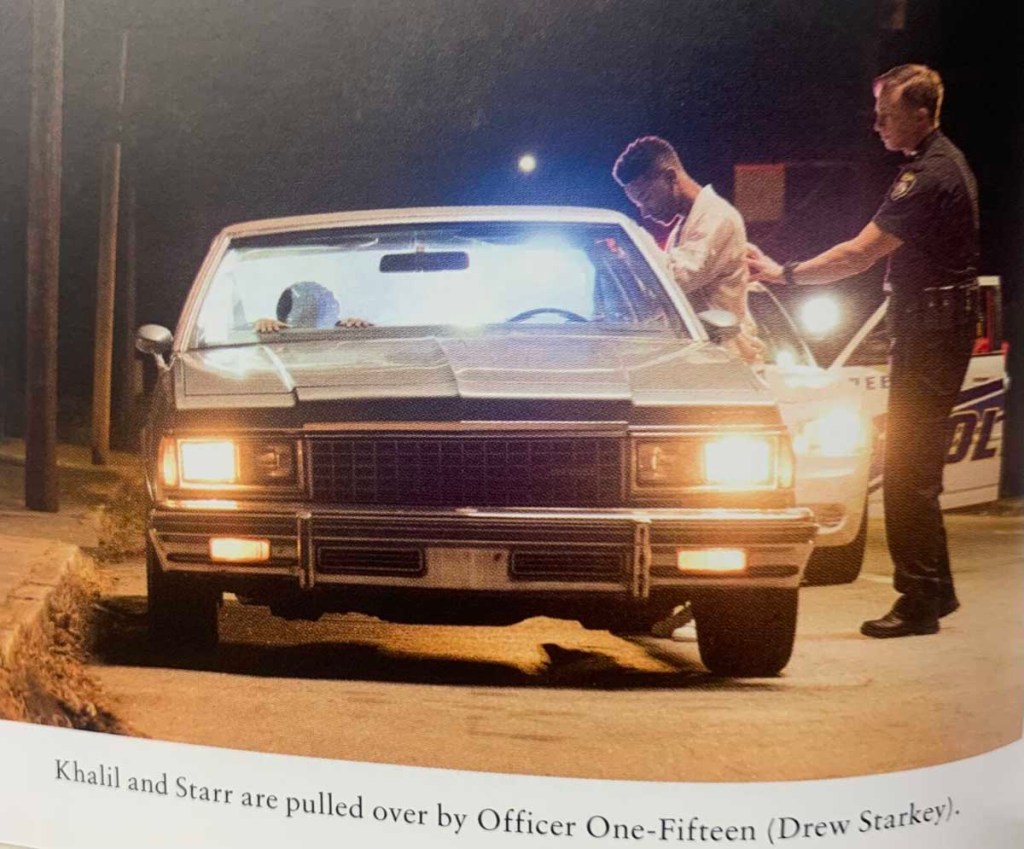

- "The Hate U Give" by Angie Thomas is among the top 10 most banned books in the U.S. schools. The book, from which the photo is extracted, follows a Black girl who witnessed the death of her Black friend who is killed by a police officer. Photo taken of a page from "The Hate U Give" by Angie Thomas

Everyone loves the hero. Kids often root for the hero.

Trending

But when that “hero” happens to be Black, that narrative often shifts.

Jerry Craft, author of award-winning “New Kid” — a book that is banned in several schools in the U.S. — knows the struggle too well.

His book and its second part, “Class Act,” are banned in several schools in the U.S. PEN America has logged seven book bans in four districts against Craft’s books, with some claims that the books are teaching critical race theory.

“What I wanted to show was the subtleties of everyday life as an African American in this country, basically,” Craft said. “So it’s not someone calling you a horrific name. It’s someone you know, touching your hair, or thinking that your dad doesn’t live with you because your mom was a single parent or, you know, getting your name wrong or, you know, just making an assumption.”

Between July 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022, PEN America reports that 41% of books banned in school libraries and classrooms contain protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color and 22% of documented book bans directly address issues of race and racism.

The “New Kid” tells the story a Black boy from Washington Heights, New York overcoming the challenges of adapting to a new predominantly white school. Craft said the book is loosely based on his experiences, along with his two sons.

The New York native said the book was not purposed to make any race feel uncomfortable or upset, but allow readers to see a Black protagonist hero. Themes in Black literature frequently relive an experience from the past or overcoming obstacles from the perspective of a Black narrative.

“If kids go to see ‘Avatar,’ the humans are bad. The little blue people are good, right? They’re rooting for the blue people. If they go to see ‘Shrek,’ they’re rooting for the green ogre. Adults are the ones that say. ‘Oh, he’s gonna be sad,'” Craft said.

“If your kid reads “New Kid” and identifies with the bully or the racist person, then you’ve not done your job as a parent because kids, generally speaking you know, they empathize and they root for the heroes,” Craft continued. “So, if you can root for blue people and green people, you can root for Black and brown people.”

Aldon Nielsen, a professor of American Literature at Penn University, said in contrast of learning about American history through the eyes of history books and newspaper articles, Black literature allows readers to experience art made from that history.

“We’re asking ourselves, not just what experiences and perspectives Black Americans had about events in American life, but how have they made sustaining wonderful artworks out of these things?” Nielsen said.

“Beloved,” a book by Toni Morrison is banned from many school libraries. Among various happenings in the book, a character separated from a plantation later tries to find the people he once had relationships with at the plantation.

“Morrison takes this actual fact of history of the way people whose lives have been disrupted and destroyed by slavery and trying to put them back together. And she put into this beautiful novel, which some schools don’t want you to read,” Nielsen said.

While well-known authors like Morrison, Octavia Butler, Ernest Gaines have books that have been banned in schools, they are best selling and award winning authors.

“Over and over again, in Black writing, you see a kind of recognition, a moment when the author comes to realize in early childhood that their race makes a social difference,” Nielsen said. “You don’t see much of that in white writing. But there has to come a moment in the lives of most white people, when they realize that there is a racial structure in this country and it means something.”

Black children especially often don’t have enough positive books that they can identify with, Craft said, speaking on the importance of Black authors.

“If these same people (supporting book bans) looked at me when I was a kid and said ‘Some of these books where all they do is show African Americans as being enslaved or in gangs or victims of police, that can’t be good for their psyche. Let’s make sure that they have books that don’t make them feel bad.’ But nobody ever protected me from these books, which is why I hated to read books as a kid,” Craft explained. “I’m like, how many books can I read on Harriet Tubman? Not that she wasn’t amazing, but that’s not someone that I necessarily identified with as a 12-year-old Black boy from Washington Heights.”

But there are many lessons that can be taken from his books by all races, he said.

“It is about respect,” Craft explained. “It’s all about taking the time to get to know someone who’s different from you.”

Amid efforts to restrict books that include race-related themes, several new book clubs have launched around the country to keep literature by Black authors in the spotlight.

A new book club at the Jack Hadley Black History Museum in Thomasville, Georgia will read its inaugural book, Nikole Hannah-Jones’s “1619 Project,” which stemmed from a project published in the New York Times in 2019. The project follows the history of the country from slavery and argues that the legacy of slavery is still embedded in various aspects of life in the U.S. today, including in the criminal justice system, housing and education. The book has been viewed by some as the model for critical race theory.

“That book also talks about Black resilience, and we don’t hear that in school,” said Cathy Hadley Wilson, programming chair for the Jack Hadley Black History Museum. “When you can get somebody that was enslaved like Frederick Douglass to be one of the best orators in American history under the conditions that he was in. And he could tell Congress this or that and they would follow suit, that’s resilience and that is something to be proud of. There’s many but we don’t know them because they just make it a blurb in the history books. They just don’t even, they don’t even tell us about our greatness. We need to know our capabilities of greatness.”

As the nation observes Black History Month in February — a designation made by every U.S. president since 1976, according to “History Channel” — recognizing Black authors and their stories amid efforts to restrict such books is among the forefront of ways to celebrate and learn Black history.

“The incredibly lively tradition of limiting Black creativity is moves to ban books,” Nielsen said. “It’s not just discussions of race that they’re trying to suppress. They’re trying to suppress blackness. It’s so important for works of literature to circulate so that there can be a continued tradition of understanding and experience.”