9/11 a “media blackout day” for former FEMA inspector

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 11, 2016

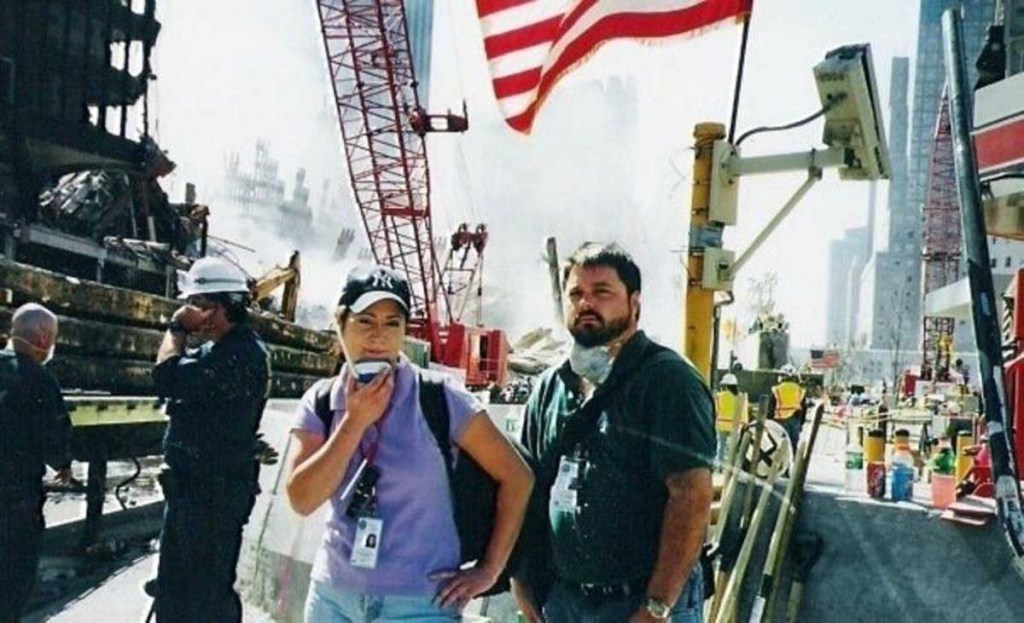

- Ranve Martinson, at left, stands amid the destruction near Ground Zero in New York City following the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks. She has few photographs from that time.

SUTTONS BAY, Mich. — Millions of televisions replayed the scene Ranve Martinson witnessed from her apartment’s rooftop:

An airliner swooping low over New York City, its engines screeching before it crashed into World Trade Center’s South Tower, sending a ball of flame and debris through the structure’s middle floors.

The towers are going to fall, Martinson told her roommate, as smoke billowed into the sky. They rushed back inside, closed their windows and watched the twin World Trade Center skyscrapers collapse on TV, one after the other. Outside the devastation blotted out the clear blue sky.

“The sky turned black,” Martinson said.

Fifteen years later she drew a black wrap tight around her shoulders inside an office at Martinson Funeral Home, a business that has been in her family for four generations, as she recalled the chilling experience. Tears welled in her eyes as she relived the horror of Sept. 11, 2001, a day on which she was the only Federal Emergency Management Agency inspector who lived in New York City.

Smoke from terrorist attacks hung over New York City, Washington, D.C., and a field in Pennsylvania 15 years ago today, events that formed a cloud that still looms over Martinson and other Grand Traverse region residents, even those too young to recall the events.

A plume of ash blew from the fallen World Trade Center across the river toward Martinson’s Park Slope apartment building. Bits of paper mixed with soot showered her fire escape. She recalled pulverized business cards that she could pluck from the air.

For a brief moment New York City was silent. And then the panic came.

Overloaded cellphone towers and a mass evacuation meant Martinson couldn’t track down friends and roommates. She called Bluebird Restaurant and Bar in Leland to check in with her brother, Nick Martinson, who was headed to New York City to visit her. It took two days for Ranve Martinson to find a friend who escaped the towers. He ended up packing his things and leaving for Boston, she said.

“He was so traumatized he moved out of New York and never came back,” she said.

Martinson managed to check her email the next day. Her FEMA bosses told her she needed to contact New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani. She walked to Giuliani’s office with a printed email telling Giuliani he needed to reopen the city’s bridges for FEMA inspectors.

“What was I, 26? I looked like I was 12,” she said. “The look on Mayor Guiliani’s face …”

Those FEMA inspectors received clearance to inspect damage to dwellings and work to give displaced New Yorkers housing. Martinson worked for Parsons Brinckerhoff, an engineering firm contracted by the agency, and entered what she called a “war zone.”

“There’s some things people shouldn’t see,” she said. “A lot of devastation, obviously. Some parts, both of the wreckage and bodies.”

Martinson recalled trudging up stairs to a man’s living room.

“He lost his pregnant wife in the North Tower,” she said. “And he has no living room wall. It’s just gaping 40 floors up into the abyss. You’re looking down at the flaming pits and steel still smoldering and the ironworkers … You know, what do you say?”

‘I lived it’

Years passed before Ranve Martinson could visit Ground Zero again.

“I’ve never really spoken much about it, that’s because it is hard,” she said. “But I had a chance last April to go back to New York and see the memorial. And that brought some closure.”

Martinson spent about a year in New York City, while her colleagues — some suffered health issues, while others burned out — cycled in and out of their duties. She never visited Suttons Bay during that time. Her work with FEMA continued until 2007, when she started mortuary school.

A move from disasters to death wasn’t that far-fetched, she said. It’s all humanity and helping people, she said.

“I get to … be back in the community and help the people that essentially raised us,” she said.

Martinson sat in an office at the funeral home, which she runs with Nick Martinson, and called the 9/11 anniversary her “media blackout day.” She plans to golf all day this year.

“The past 14 years on the anniversary, I don’t need to see that on the TV,” she said. “I lived it.”

Troutman writes for the Traverse City, Michigan, Record-Eagle.