World War II-era case from Ga. city informed religious freedom debate

Published 7:20 am Monday, April 11, 2016

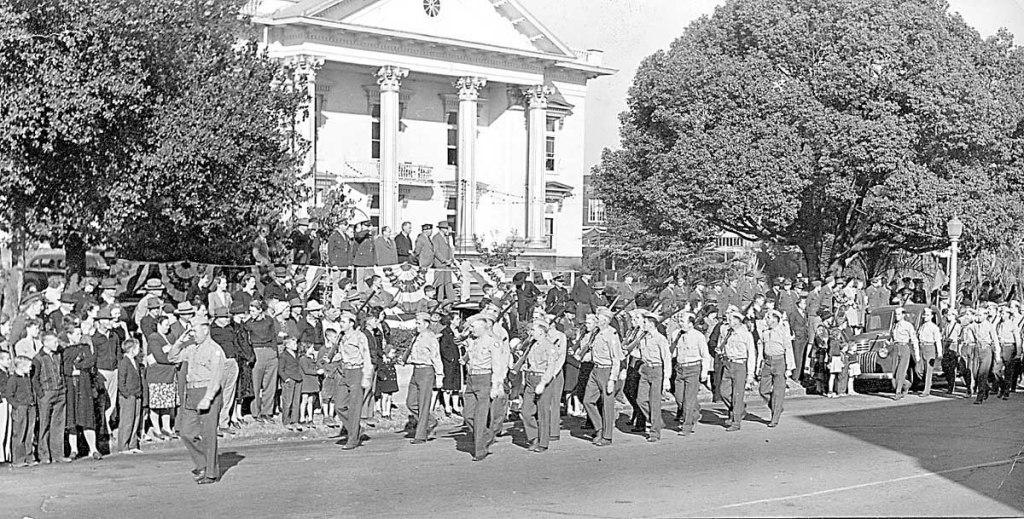

- Moultrie, Georgia units of the Georgia State Guard march in a parade on Armistice Day, Nov. 11, 1942.

ATLANTA — Three men stood on a busy Moultrie, Georgia sidewalk with a stack of religious magazines and insisted on their right to be there.

The city’s attorney and police chief were just as adamant. They vowed to arrest the men, who were Jehovah’s Witnesses, every time they tried to sell magazines in Moultrie’s crowded square.

Trending

It took the state Supreme Court to resolve this stalemate, handing a victory to the city. The court ruled that the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ religious freedom did not trump the city’s efforts to maintain law and order.

Seven decades later, the core principle cited in that 1943 decision — that one person’s rights end where another’s begins — still echoes under the Gold Dome as lawmakers debate the boundaries of personal religious freedom.

Proponents of a religious freedom bill this spring invoked the old case in response to critics who claimed the law would lead to discrimination against lesbians and gays. Gov. Nathan Deal has since vetoed the bill.

“You ought to be able to believe what you want, and you ought to be able to exercise the tenets of your faith the way you see fit,” said Rep. Christian Coomer, R-Cartersville, from the House floor last month. “But there is a limit on that, and the limit is you can’t invade the rights of others when you do it.”

That principle, Coomer said, would act as a safeguard from discrimination.

But there’s a danger in relying on a 72-year-old opinion — one of few issued on free religious exercise in Georgia, for that matter, said Anthony Kreis, a professor at the University of Georgia.

For one, it’s unclear how a judge today might apply the ruling, he said, adding that protections are better plainly stated in the law, leaving less room for interpretation.

Still, Kreis said the Moultrie decision is significant partly because it establishes that a person’s right to religious freedom cannot be allowed to hurt others.

The impact of the case, Jones v. the city of Moultrie, is also blunted by a major question that lingers in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision affirming the right of same-sex couples to marry.

“The principle is right from the Moultrie case — that third-party harms are wrong and are beyond the bounds of what constitutes acceptable religious liberty,” Kreis said. “What still hasn’t been settled is, what are the harms?”

In other words, who really suffers — a florist who provides an arrangement for a same-sex marriage in spite of religious objections, or the same-sex couple who is turned away?

Seven decades ago, the Jehovah’s Witnesses were on the losing side of that question.

The population of the southwest Georgia city, the seat of Colquitt County, swelled after the opening of a new airfield during World War II.

City officials saw the result as nothing short of a crisis.

Thousands of soldiers and civilian personnel moved into the area, testing the limits of roadways and doubling foot traffic downtown.

Farmers, airmen and others would gather at the courthouse square on Saturdays to shop, catch a movie, grab a hamburger or just let loose with friends and family.

“They would walk the streets, because there was nothing else to do,” said Grace Taylor, a 93-year-old, lifelong resident of Moultrie. “People would walk and eat those hamburgers.”

City officials passed ordinances to manage this surge, including a local law barring people from hawking their wares near the courthouse on Saturdays — a prohibition that the Jehovah’s Witnesses argued should not apply to them.

The court disagreed.

“A person’s right to exercise religious freedom, which may be manifested by acts, ceases where it overlaps and transgresses the rights of others,” the court concluded.

Taylor was 21 when the ruling was issued. She doesn’t recall it.

The local history museum also had nothing on it.

But the case found a prominent spot during debate this session on the religious freedom bill.

That measure would have, among other things, allowed faith-based groups, such as religious schools, to deny services if doing so violated their beliefs. It would have made clear that pastors cannot be required to officiate at a same-sex wedding. Also, it said individuals could not be forced to attend such weddings.

The bill’s final version included what Coomer called a “guidepost” for future judges. The Legislature, he said, meant for the bill to be consistent with the Moultrie decision.

Rep. Stacey Abrams, D-Atlanta, countered: “When we have to have guideposts, we are usually on the wrong road.”

A religious freedom measure will most certainly reemerge in the next legislative session, with supporters pressing for protections for the faith community — including business owners.

John Carlton, a Moultrie attorney whose firm represented the city for several decades, said he thinks the state should just stay out of it.

“To say somebody would not bake a gay wedding cake, and you need some state protection for that, is goofy. He just doesn’t have to do a wedding cake,” he said.

Jill Nolin covers the Georgia Statehouse for CNHI’s newspapers and websites. Reach her at jnolin@cnhi.com.